The meta-circular evaluator

Meta-circular evaluators are awe-inspiring.

This will be a walkthrough of the meta-circular evaluator demonstrated in Chapter 4 and Lecture 7A of The Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (SICP). The chapter and video are on the subject of "meta-linguistic abstraction" – the establishing of new languages.

To evaluate a computer language you need an evaluator (also called interpreter) for that language. Evaluating an expression in a programming language means that the evaluator performs or executes the instructions described in the expression. An evaluator is called meta-circular if it evaluates the same language as it is written in using the same language constructs as the language itself (circular definitions).

Why would you want such a thing? One of the reasons is that having a meta-circular evaluator makes it very practical to implement new languages on top of the implementation language. Using a meta-circular evaluator you can, for example, create a language that is particularly suited for a problem at hand (a Domain Specific Language). Another reason is that it is insightful for educational and experimental purposes. The basic eval-apply structure below can be used to write interpreters for all kinds of languages. It is the kernel for every computer language.

What does a meta-circular evaluator look like? In SICP it is stated that:

It is no exaggeration to regard this as the most fundamental idea in programming:

The evaluator, which determines the meaning of expressions in a programming language, is just another program.

So it is just another program. In this post I have translated the code from meta-circular evaluator program from SICP (you can find the original code here) to Clojure.

Clojure is interesting because:

- It runs on the Java Virtual Machine (therefore having access to all Java libraries and being able to interoperate with existing Java code bases).

- It has a functional core (therefore being particularly suited for concurrent programming, necessary to utilize multiple CPUs).

- And it is a dialect of Lisp (therefore having all the interesting properties described below).

Now, before I continue, let me be clear. I am not an expert on the subject matter. It is impossible for me to improve on the explanation in SICP. What I have attempted to do here is translate the Scheme code of SICP to Clojure and thereby deeper understand what is going on in the meta-circular evaluator and also learn something about Clojure. I have tried to put into my own words what is described in SICP. If you have a background in computer science this post is probably not much new. After all, SICP is an introductory level computer science book. I don't have such a background so for me this was all pretty mind blowing. I learned quite a lot from this post myself. Before I started to write I thought I understood, but when converting the SICP code to Clojure I realized I did not understand it as thoroughly as I thought. I needed quite a lot of help from the web and the end result is basically different sources copy-pasted together till I had a reasonably working evaluator.

It is very likely that the text in this post contains mistakes and I would be happy if they will be pointed out to me as well.

Now, let's get started.

Background

The idea of a meta-circular evaluator was first described by John McCarthy in his paper Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I.

(There has by the way never been a Part 2, although some people have some ideas what it would look like).

This is the paper where McCarthy invented Lisp (acronym for LIst Processing). It contained the definition for eval – the universal function. eval is a universal machine: if you feed it a Lisp program, eval starts behaving as that program. It required inventing a notation where you could represent programs as data.

For McCarthy, writing this function was just a theoretical exercise. It was never his idea that the language or the function was actually implemented. What then happened was that Steve Russell, one of McCarthy's graduate students (who also invented one of the first computer games) transformed his theory into an actual programming language. As McCarthy stated in an interview:

Steve Russell said, look, why don't I program this eval..., and I said to him, ho, ho, you're confusing theory with practice, this eval is intended for reading, not for computing. But he went ahead and did it. That is, he compiled the

evalin my paper into IBM 704 machine code, fixing a bug, and then advertised this as a Lisp interpreter, which it certainly was. So at that point Lisp had essentially the form that it has today..." (Source)

Alan Kay (famous computer scientist and creator of the language Smalltalk) describes his excitement when he first saw this eval and understood that it was Lisp written in itself.

These were "Maxwells Equations of Software!" This is the whole world of programming in a few lines that I can put my hand over.

Note: the Maxwell equations are four extremely elegant equations from which everything there is to know about the electromagnetic field can be derived.

Lisp is special because it does not enforce syntactic and semantic rules: it can be programmed at a higher level of abstraction than other languages. Lisp can be transformed in other languages. Some of that we will see below.

So what does Lisp look like?

Lisp, Lisp, Lisp

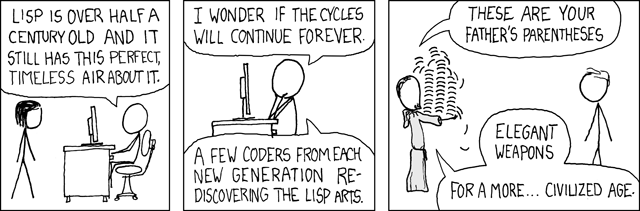

The nice thing about Lisp is that is has almost no syntax. The rules are simple (like Go), but the possibilities within these rules are virtually endless (like Go). Lisp is infamous for its parentheses.

(Source: https://xkcd.com/297/)

Combined with prefix notation these parentheses makes it so that Lisp data structures have the same makeup as Lisp code. The fundamental data structure in Lisp is a list (in Clojure we have some more data structures, we will not worry about that now). The first part of a list is interpreted as the operator, and the rest as the operands.

So for example in:

(+ 1 2 (* 3 4))

The operator is + and the operands are 1, 2, and (* 3 4). Lisp applies the operator to the operands and this leads to the result of 12 in the case of (* 3 4) and 15 in the case of (+ 1 2 12).

The abstract syntax tree (AST) looks like this:

(Source: https://github.com/jiacai2050/JCScheme)

As can be seen the AST of Lisp is the same as Lisp itself. A Lisp is a language that is written in an AST, when the language is interpreted or compiled these code trees can be manipulated.

Now, let's look at the seven or so special forms of the language. The rest of Lisp can be implemented in these special forms. (Note: in reality Lisp is not implemented this way, there are some more special forms used in most Lisps for for example performance and usability reasons).

My description of these special forms (from which eval can be created) is roughly based on the article Roots of Lisp of Paul Graham where he explains what McCarthy has discovered. The original definitions of McCarthy can be found here.

In Lisp there are about seven fundamental forms:

atom

Everything in Lisp is either a list or an atom. (In Clojure we also have some other types like vectors, but we do not worry about that.) Atoms are for example numbers (1), strings ("hello") or symbols (add1). Lists consist of parentheses surrounding atoms separated by whitespace or other lists or both.

quote

Quoting an expression means that the expression does not need to be evaluated. This is similar to our use of quotes in natural language, where we use quotes to refer to the symbol itself instead to the meaning. To "say your name" I reply with "Erwin", to "say 'your name'" I reply with "your name". The quote operator can be used to blur the distinction between code and data. By quoting code you can pass it as data to another method which can then inspect and evaluate the expression. To quote you can use the operator quote or put a ' in front of the expression.

Example: '(+ 1 2 3). Which is equal to (quote (+ 1 2 3)). When this expression is evaluated the result is (+ 1 2 3) (instead of 6, the result of evaluating the unquoted (+ 1 2 3)).

eq? a b

(eq? a b) returns true if the values of a and b are the same atom or both the empty list (defined as '()), and false otherwise.

cons a l

cons stands for construct and is used to add one element a to a list l. Lisp lists are chains of cons cells, where the second element points to the first element of the next cons cell (a linked list). The last element of a list is the empty list '() (or nil).

Note that Clojure does not use the cons cell as described above to create a list. Clojure has sequences. Again, we will not worry about that now since the operations supported are similar, only the underlying implementation is different.

car l

(car l) returns the first item in a list. In Clojure this form is called first.

cdr l

(cdr l) returns everything but the first item in a list. In Clojure this form is called rest.

car comes from "Contents of the Address part of Register number" and cdr from "Contents of the Decrement part of Register number". They refer to the way cons cells were stored in early computers. This is no longer the way it is, but Lispers have decided to stay with it because you can easily combine them. E.g., the car of the cdr (the second element of a list) is the cadr. Clojure breaks this connection with these roots, but has introduced other forms to make it easier to chain methods together (e.g., ->) and has special utility methods like nth to obtain the nth element from a list.

cond <p1> <e1> ... <pn> <en>

A conditional (conditionals were among other things first introduced in the paper of McCarthy). If pn is true en is evaluated. Also an :else clause can be introduced if no predicates are true.

So in (cond (p<sub>1</sub> n<sub>1</sub>) (p<sub>2</sub> n<sub>2</sub>) :else "Hi") the result is n1 if p1 is true, n2 if p1 is false, and p2 is true, and "Hi" if both p1 and p2 are false.

Besides these fundamental forms you can create functions with fn. In a function you have a list of arguments and a list of expressions. The value of the arguments are assigned to the values that are passed during the function call (this becomes relevant later). A lambda expression (anonymous function) is created like this:

(fn (arg) (+ arg 1))

((fn (arg) (+ arg 1)) 1) ;; => 2

This can be read as "call the lambda expression with argument arg and body arg plus 1 with the argument 1 substituted for arg, resulting in (+ 1 1) which evaluates to 2".

Expressions can be bound to a symbol in Clojure with defn as follows:

(defn add1 [arg]

(+ arg 1)))

Here add1 with argument arg is bound to (+ arg 1).

As said Clojure has more collection types than the list. Clojure also contains maps, vectors and sets.

It is interesting to note that these other data structures are implemented in Clojure in such a way that they are immutable (unchangeable). And because they share underlying structures when being copied they have very good performance characteristics. To learn some more about this you can view a video where the creator of Clojure explains this how these data structures are implemented.

One more thing you will see in the implementation below: some data structures are demarcated by different types of symbols. The vector uses the [ and ]. In Clojure the argument list to a function or definition is a vector (not a list) and looks like this:

(fn [arg] (+ arg 1) 1) ;; => 2

Since it supports the same basic operations as a list (like first, empty, or rest`) it is fine to think about it as a list.

Example of use: implementing map

To define functions and to evaluate them often recursion is used. Below we will define a procedure that is called map. map applies a given function f to every argument in a list (coll) and returns a list with the results. So when we do (map add1 '(1 2 3)) (using add1 defined above) the result will be (2 3 4).

(defn map [f coll]

(if (empty? coll) '()

(cons (f (first coll)) (map f (rest coll)))))

This is done by cdring ("resting" in the case of Clojure) down a list and consing up the result. It applies f to the first element of the list, and combines (cons) the result with f mapped to the rest of the list. The recursion breaks if the collection is empty. The evaluator has a lot of these type of recursive definitions as well so it is crucial to understand.

The seven forms above (map is not a primitive) are all the primitives you need to create a meta-circular evaluator.

Now, in an actual Lisp implementation there are a lot more primitives. The code belows also uses more forms. Most of them can be implemented in the code below, but others can't. The reason for that is that sometimes the evaluation order matters.

Another form we will see is let, which is of the form

(let [<var1> <val1> <varn> <valn>] <body>)

let can be used to bind variables (var) to value (val) (to declare variables basically). These are in scope in the body. This let can roughly be written as:

((fn [<var1> <varn>] <body>) <val1> <valn>)

Where you create a lambda where the variables are substituted for the values.

This is impossible to implement in a normal function, since the variables are always evaluated. When evaluation order needs to be controlled, a so-called macro can be created.

A macro hooks provides a convenient way to hook directly into the abstract syntax tree and change it at compile time (before the code runs). We will not be using or supporting macro's in this meta-circular evaluator, but it is definitely possible. If you want to learn more about macros you can read Paul Graham's On Lisp or Doug Hoyte's Let Over Lambda.

Now we have defined all the basic operators. Let's look at the meta-circular evaluator.

The implementation of the meta-circular evaluator

The meta-circular evaluator consists of two methods: eval and apply.

These methods call each other recursively as follows. This can be displayed as follows:

(Source: https://github.com/jiacai2050/JCScheme)

If no descriptive names are used for definitions inside eval and apply, the whole evaluator fits on one page. As shown in the Lisp manual (p. 13) it fits on one page, and as demonstrated in SICP lecture 7A: on a blackboard. In the current implementation a bit more descriptive names are used since it helps for clarity. And also a somewhat sophisticated environment structure is used to store procedures. Therefore this code does not fit on one page, but it is definitely still a short program.

Unfortunately the implementation described below is possibly not truly a meta-circular evaluator. A defining characteristic of a meta-circular evaluator is that it is written in the language it evaluates. This evaluator is written in Clojure, but it cannot evaluate everything of Clojure. What it can evaluate looks a lot like Scheme translated to Clojure, because in fact it is. But... Since Clojure is a Lisp and Scheme is a Lisp, I think the name meta-circular evaluator is still warranted.

Now we will implement eval and apply.

Eval

eval is a procedure that takes two arguments: an expression and an environment. And like every interesting procedure, it is a case analysis:

(defn eval [exp env]

(cond (self-evaluating? exp) exp

(variable? exp) (lookup-variable-value exp env)

(quoted? exp) (text-of-quotation exp)

(assignment? exp) (eval-assignment exp env)

(definition? exp) (eval-definition exp env)

(if? exp) (eval-if exp env)

(lambda? exp) (make-procedure (lambda-parameters exp)

(lambda-body exp)

env)

(begin? exp) (eval-sequence (begin-actions exp) env)

(cond? exp) (eval (cond->if exp) env)

(application? exp) (apply (eval (operator exp) env)

(list-of-values (operands exp) env))

:else (error "Unknown expression type -- EVAL" exp)))

When we call eval with a quoted expression to evaluate (e.g., (eval 'definition 'env) in an environment, it will look at what type of expression we are dealing with, and then dispatch to another procedure to handle it.

I'll first go over it just describing eval in words, and next dive deeper into the routines. When an expression exp is self-evaluating (like a string ["hello"], a number [1] or a boolean [true]) eval just gets the expression back. If exp is a variable (a), we look up the value of the variable in the environment (we will discuss how this works later). If exp is a definition we want to define the value in the environment. (If we define (defn a "hello") we want "a" stored in the environment to be "hello", and when we look up the variable a later we want to have "hello" returned.) If exp is an assignment (set! a "hi"), we will look up a in the environment, and set it to a new value. If exp is a lambda expression (anonymous function) we create a procedure of this lambda expression (we create a list tagged with the flag 'procedure), where we store the parameters and the body of the procedure alongside with the current environment captured in it (see make-procedure below). Next, we have an if-statement and conditional: a conditional is transformed to a list of if-statements via a routine named cond->if. In an if-statement: if the predicate is true the first clause is evaluated, and if false the second clause is evaluated. For example, (if p 'n<sub>1</sub> 'n<sub>2</sub>) leads to n<sub>1</sub> if p is true and to n<sub>2</sub> otherwise.

The above is all reasonably straightforward. It is a way to implement all the reserved words. As an aside, Gerald Jay Sussman states:

The number of reserved words that should exist in a language should be no more than a person can remember on its fingers and toes. I get very upset with languages which have hundreds or reserved words. (Source)

If the expression does not start with a reserved word, the expression is an application. This means we apply the result of evaluating the operator of the expression in the environment, to the list of values that follow, each evaluated in the environment.

First we look at list-of-values, which is implemented as follows:

(defn list-of-values [exps env]

(if (no-operands? exps)

'()

(cons (eval (first-operand exps) env)

(list-of-values (rest-operands exps) env))))

This is a recursive definition (like map above) where we construct a new list with as first argument the first operand evaluated in the environment, and as the rest, the rest of the operands evaluated in the environment. When we come to the empty list '() (the second element of the last cons cell in a linked list) the recursion breaks and we return the empty list '().

We will discuss the implementation of apply after we have looked at the inner definitions of eval a little bit closer. These consist of routines to detect expression, routines to get information out of expressions, and routines to transform expressions.

Routines to detect expressions.

First a little heads up: all definitions used above to get information out of expressions (like first-operand and rest-operands) are all implemented with cars and cdrs (first and rest in Clojure). E.g.,

(defn first-operand [args] (first args))

(defn rest-operands [args] (rest args))

(defn no-operands? [args] (empty? args))

Detecting what type of an expression we are dealing with, is done by comparing the first element of the list via tagged-list:

(defn tagged-list? [exp tag]

(and (list? exp) (= (first exp) tag)))

This checks if the expression is a list, and (using the code inspecting facilities of Lisp) if the first expression is equal to the tag.

For example, to see if a variable is a definition or quoted we check if the first element is respectively the symbol 'quote or 'defn:

(defn quoted? [exp] (tagged-list? exp 'quote))

(defn definition? [exp] (tagged-list? exp 'defn))

And in a similar manner:

(defn lambda? [exp] (tagged-list? exp 'fn))

(defn assignment? [exp] (tagged-list? exp 'set!))

(defn begin? [exp] (tagged-list? exp 'do))

(defn true? [x] (not (= x false)))

(defn false? [x] (= x false))

(defn cond? [exp] (tagged-list? exp 'cond))

(defn compound-procedure? [p] (tagged-list? p 'procedure))

(...)

?.This is how routines to detect expressions are implemented.

Routines that get information out of expressions

Beside routines to detect expressions we have some procedures to get information out of expressions. We know the syntax of our language and we know at which position certain elements should be located. First we define some helper methods to get certain elements out of a list besides the rest and the first, so for example the second is:

(defn second [exp] (first (rest exp))) ; cadr

(defn rest-after-second [exp] (rest (rest exp))) ; cddr

(...)

These routines are implemented in Clojure as follows:

(defn operator [exp] (first exp))

(defn operands [exp] (rest exp))

(defn text-of-quotation [exp] (second exp))

(defn assignment-variable [exp] (second exp))

(defn lambda-parameters [exp] (second exp))

(defn lambda-body [exp] (rest-after-second exp))

(...)

Here we see that for example lamba-body is the rest-after-second. Which is indeed the case. If we look at:

(fn [a b c d] (+ a b (* c d)))

We see that everything after the second element (a b c d) is the body.

All the other implementations of routines that get information out of expressions are defined in the same manner.

Routines to manipulate expressions

As seen in the definition of eval above, when an expression is a lambda expression (as identified by lambda?), we make a procedure. This is implemented as follows:

(defn make-procedure [parameters body env]

(list 'procedure parameters body env))

So we create a new list via the procedure list (which is a routine to create a linked list via a chain of cons'es). Note that the procedure creates a new list where the environment is stored in. This is a way to create something called a closure: the environment at the moment the procedure was called is captured. Next when we look at apply we will see how this environment is retrieved. Furthermore, we will discuss the difference between two types of scope (dynamic and lexical) and their implementation later.

In a similar manner as make-procedure we can create a new type of expression from an if-expresion in cond->if.

Note: using -> is a convention to signify the routine is a conversion.

Via cond->if a cond expressions (conditional) can be converted using an internal procedure named expand-clauses. expand-clauses recursively expands every clause of a cond expression to nested if-statements.

So eval evaluated an expression by detecting the type of expression, getting the information out of the expression and possibly converting it to something else, If it does not start with one of the reserved words it is treated as an application. This will be handled with apply in the next segment.

Apply

We have arrived at apply. apply is called in eval if the expression is not one of the reserved words (like if, cond, fn, defn and set!). An expression is an application if it is not one of the special forms, but still a list (e.g., in the case of (+ 1 2), + is not in the list of the reserved words). Then the expression will be handled by this part of eval (see above):

(...)

(apply (eval (operator exp) env)

(list-of-values (operands exp) env)

(...)

We already looked at list-of-values that evaluated all the operands in an environment. What remains is applying the operator to the arguments. apply then feeds back the expression and the environment to eval, et cetera.

apply is a procedure that takes as input a procedure and its arguments, and produces an expression and an environment:

(defn apply [procedure arguments]

(cond (primitive-procedure? procedure)

(apply-primitive-procedure procedure arguments)

(compound-procedure? procedure)

(eval-sequence

(procedure-body procedure)

(extend-environment (procedure-parameters procedure) ; variables

arguments ; values

(procedure-environment procedure))) ; base environment

:else (error "Unknown procedure type -- APPLY" procedure)))

Again it is a case analysis. Let's go through it. We first check if a procedure is a primitive procedure with primitive-procedure?. A procedure is a primitive procedure if it is looked up in the environment and it was in the list of primitive procedures defined in the environment. The primitive procedures are defined as follows, and are later added to the environment (how the environment is constructed will be discussed later).

(def primitive-procedures

(list (list 'first first)

(list 'rest rest)

(list 'cons cons)

(list 'nil? nil?)

(list 'empty empty)

(list 'list list)

(list '+ +)

(list '- -)

(list '* *)

(list '/ /)

;; more primitives

))

If the procedure is a primitive procedure we apply the primitive procedure with the underlying apply of Clojure. At the beginning of the evaluator we store the underlying apply to not confuse it with the newly defined apply:

(defn apply-from-underlying-lisp [procedure arguments] (apply procedure arguments))

How this apply that is built into Clojure works, is outside of the scope of this post (to be honest I don't know). Interesting to note is that these types of primitives are not essential for computation. You can do everything with lambda and something called a Y Combinator. But using that is not as convenient.

The application of a primitive procedure is defined as follows:

(defn apply-primitive-procedure [proc args]

(apply-from-underlying-lisp

(primitive-implementation proc) args))

Where primitive-implementation is a method to retrieve the procedure:

(defn primitive-implementation [proc] (second proc))

As can be seen above where the primitives-procedures are defined the primitive-implementation is a symbol like first or +. Again, these are evaluated by the underlying Clojure implementation.

If we are dealing with a compound procedure (a list tagged with procedure), we evaluate the sequence of elements with the routine eval-sequence:

(defn eval-sequence [exps env]

(if (last-exp? exps)

(eval (first-exp exps) env)

(do

(eval (first-exp exps) env)

(eval-sequence (rest-exps exps) env))))

Note that do is used to evaluate multiple expressions (in eval it is detected by begin?, a similar construct in Scheme).

eval-sequence is a recursive definition where we, if we have only one expression, only evaluate this one expression in the environment, and if we have more than one expression, we evaluate the first expression and eval-sequence the rest of the expressions in the environment.

Here last-exp, first-exp and rest-exp are defined as follows:

(defn last-exp? [seq] (empty? (rest seq)))

(defn first-exp [seq] (first seq))

(defn rest-exps [seq] (rest seq))

Naturally the first expression is the first element of the sequence (of expressions). The rest of the expressions is the rest of the sequence. And we are dealing with the last expression if the rest of the sequence after it is empty.

Important to note is that when we use eval-sequence in the definition of apply we extend the environment of the evaluation with the procedure parameters, arguments, and the procedure environment itself. This way the environment of the procedure (which was stored when it was created) are available during evaluation.

So what exactly is this extending of an environment? And in what way are symbols added to it?

The environment

We now go step by step through the environment.

An environment consists of frames stacked together in a list. A frame is empty or consists of two lists: one lists with variables, and one list with values. When a definition is looked up we look at the first frame to see if the variable is defined there. If we find it we return the value. If it is not, we look one frame further to see if it is defined there. Until we finally get to the global environment. If it is not found there we have an error ("Unbound variable"). So the goal of an environment is to store variables and the values associated with them.

A simple environment structure looks like this:

Source: https://mitpress.mit.edu/sicp/full-text/book/book-Z-H-21.html#%sec3.2.

Here we see multiple frames (I, II and III) that are connected. A will find that the value of the variable x is 7, but C will find 3.

The environment is crucial to the evaluation process, because it determines the context in which an expression will be evaluated. Each time a procedure is applied, a new frame is created.

It turns out that my assumed immutability (I thought nothing could be changed, which was not completely true from a user's perspective) of Clojure made the implementation quite difficult (for me). Clojure has, unlike Scheme (the language where this evaluator was translated from), no mutable (changeable) cons cells (no actual cons cell at all as described earlier). Where in Scheme you can change the first element or last element of a list respectively with the routines set-car! and set-cdr!, this is not possible in Clojure.

We can however accomplish mutation by defining a so-called Atom (different from the basic building element atom defined above). An Atom in Clojure is a mutable value, that can be mutated in an atomic way, free of concurrency problems (see this chapter on Metaphysics in Clojure for the Brave and True for an explanation).

The algorithm used in the Scheme version checks the first frame, loops over it (with a method called scan) and if it finds the variable, it returns the value associated with it. If it does not find anything it will loop over the enclosing environment and scans there.

When redefining a variable in the environment, a similar process is used. When the variable is found however, set-car! is used to overwrite the variable value in that frame.

After using some environment structures with bugs in them (for example being unable to define recursive definitions) I found a better environment definition in the SICP answers of Jake McCrary. The implementation has the same behavior as that of the original of the SICP.

We now go step by step through this environment structure by Jake McCrary.

The empty environment is an empty list.

(def the-empty-environment '())

(Note that def is similar to defn without arguments.)

To get the enclosing environment (frame) of the current environment (frame), we look at the rest from the frame we are in now.

(defn enclosing-environment [env] (rest env))

(defn first-frame [env] (first env))

To make a frame, we use a routine zipmap to add two lists of variables together which "returns a map with the keys mapped to the corresponding vals" (ClojureDocs). A map is a list of key-value pairs.

(defn make-frame [variables values]

(atom (zipmap variables values)))

(defn frame-variables [frame] (keys @frame))

(defn frame-values [frame] (vals @frame))

Let's illustrate the behavior of this creating of frames with zipmap.

We have a list of variables to be added to the environment:

(def variables (list '+

'rest

'add1))

A list of corresponding values (the primitive + and rest operator, and a lambda expression and a created procedure to be added to the environment:

(def values (list +

rest

'(fn (x) (+ x 1))

'(procedure (x) (fn (x) (+ x 1)) {:+ + :x 2 (...)})))

When we zipmap them:

(zipmap variables values)

This leads to the following result:

So a frame is a map (key value pairs, differentiated with{+ #object[clojure.core$PLUS (...)],

rest #object[clojure.core$rest_ (...))],

add1 (procedure (x) (fn (x) (+ x 1)) {:+ +, :x 2, (...)})}

{ and } in Clojure) with variables (keys of the map) bound to values (values of the map) (in this case the primitive objects from the underlying Clojure).Next we get methods to add bindings to frames:

(defn add-binding-to-frame! [var val frame]

(swap! frame assoc var val))

Note that by convention routines that mutate state are ended with an exclamation mark !.

add-binding-to-frame! uses swap! in combination with assoc to associate a variable and new value to a frame. This is one of the ways to have (safe) mutable state.

Next we need a way to extend our environment (this is the method used in eval and eval-sequence to add variables and values to a frame, for example when storing the variables of a procedure in the environment where it will be evaluated in, or when new definitions are added):

(defn extend-environment [vars vals base-env]

(if (= (count vars) (count vals))

(cons (make-frame vars vals) base-env)

(if (< (count vars) (count vals))

(error "Too many arguments supplied " vars)

(error "Too few arguments supplied " vars))))

extend-environment takes variables and values and a base environment. It then makes a frame of the variables and values and conses that up to the base environment. The rest is error handling for when the amount of variables and values applied are not the same (e.g., when evaluating ((fn (x) (+ x 1)) 2 3) it will returns "Too many arguments supplied").

Next, we have a method to lookup a variable in an environment. This one looks a bit more complicated because of the inner methods.

Know that letfn is just like let, only now we define functions and bind them to a name only available in the scope. Furthermore, contains? checks if a variable is available in a map and returns true if it does, false it it does not.

(defn lookup-variable-value [variable env]

(letfn [(env-loop [env]

(letfn [(scan [frame]

(if (contains? frame variable)

(let [value (get frame variable)]

value)

(env-loop (enclosing-environment env))))]

(if (= env the-empty-environment)

(error "Unbound variable -- LOOKUP" variable)

(let [frame (first-frame env)]

(scan @frame)))))]

(env-loop env)))

What happens at the bottom of lookup-variable-value is that we start an env-loop with the env. env-loop defines a method scan to look for a variable in a frame.

If the frame contains the variable we get (get is a way to retrieve the value belonging to a key) the value belonging to the variable from the frame. Otherwise, we start a new env-loop over the enclosing environment (the next frame or frames).

When the env-loop is started we first check if we are dealing with the empty environment. If that is the case we break the recursion: we have scanned all frames in scope and we are therefore dealing with an unbound variable. If we are not dealing with the empty environment, we are getting the first frame from the (remaining) environment (remember that the environment is a list of frames), get the value from the atom by using @, and scan that.

So now we can understand how to lookup a variable, we also need a way to define a variable value in the environment. To accomplish this we have a similar procedure, which uses a similar scanning method as above.

(defn set-variable-value! [variable value env]

(letfn [(env-loop [env]

(letfn [(scan [frame]

(if (contains? @frame variable)

(swap! frame assoc variable value)

(env-loop (enclosing-environment env))))]

(if (= env the-empty-environment)

(error "Unbound variable -- SET!" variable)

(scan (first-frame env)))))]

(env-loop env)))

The difference with lookup-variable-value is that in set-variable-value! we are trying to find the variable, and in the first frame we find which contains the variable we change this variable's value for the current value. If the frame doesn't contain it we start the env-loop over the enclosing environment. The recursion breaks when we end up with the empty environment (unbound variable) or when we find a variable and have set it.

Furthermore,to define a variable we get the first frame of the environment and add the variable as a key with the value as a value. (So we add it to the top-level frame, the global environment.)

(defn define-variable! [variable value env]

(swap! (first-frame env) assoc variable value))

Finally, at the beginning we setup the environment:

(defn setup-environment []

(let [initial-env

(extend-environment primitive-procedure-names

primitive-procedure-objects

the-empty-environment)]

initial-env))

We load the primitive procedures in the environment and we set the-empty-environment as our base environment.

Now you've seen everything but a way to interact with this evaluator.

Interacting with the evaluator

Last but not least we have a way to interact with the evaluator. When we run the code a driver-loop asks for input, and when it has received input it will evaluate the input in our environment:

(def input-prompt ";;; Eval input:")

(def output-prompt ";;; Eval value:")

(defn driver-loop []

(prompt-for-input input-prompt)

(let [input (read)]

(user-print input)

(let [output (eval input the-global-environment)]

(announce-output output-prompt)

(user-print output)))

(driver-loop))

(defn prompt-for-input [string]

(newline) (println string) (newline))

(defn announce-output [string]

(newline) (println string) (newline))

(defn user-print [object]

(if (compound-procedure? object)

(println (list 'compound-procedure

(procedure-parameters object)

(procedure-body object)

'<procedure-env>))

(println object)))

'METACIRCULAR-EVALUATOR-LOADED

(def the-global-environment (setup-environment))

(driver-loop)

That's it. Works like a charm.

Example interaction

The goal of this thing was to be able to feed the evaluator program a Lisp expression, and have it return the result. So when we feed it (eval '(defn add1 (fn (x) (+ x 1))) <e>) it should know what this means and add the symbol add1 to the environment.

Here we see some interactions with the evaluator:

So "Hello" evaluates to itself since it is self-evaluating. + is found in the environment and termined to be a primitive operation from the underlying Clojure. And we can also define functions like map and add1 and apply these to arguments.

If you would like to see a full evaluation of an expression by hand, I can recommend watching the second part of Lecture 7A of SICP. You can also run the code of the evaluator and put some break points or printlns at strategic points.

Dynamically scoped environment

In my journey to create a working version I also stumbled upon this implementation of Mathieu Gauthron.

A dynamically scoped environment is a bit simpler to implement, what is defined latest is found first (instead of passing an environment along in a certain procedure scope, we just update the environment). It is a bit harder to reason about though, because in a dynamically scoped environment it is only at runtime defined what is in scope.

After we define what lexical and dynamic scope is, below will follow an experiment with the dynamic evaluator.

Lexical scoping versus dynamic scoping

Lexical scope means that the structure of the program determines which variables are in scope (for example in C-like languages the scope is defined by curly braces { and }. In dynamic scope the scope is defined at runtime, that what was defined latest when the program is evaluated at runtime is found first. Currently there are almost no languages with dynamic scope. Lexical scope is more logical to reason about. Nevertheless there are valid use cases for dynamic scope. A nice example is exception handling (throwing an exception and catching it):

One way to test if a language is dynamic or static is by the following idea:Exception handling in most languages utilizes dynamic scoping; when an exception occurs control will be transferred back to the closest handler on the (dynamic) activation stack.

First you define a method that uses a variable scope in its body:

(defn test (fn [] scope))

(test)

this returns

Is not a valid symbol – LOOKUP-VARIABLE-VALUE scope

This is because scope is not available in the environment. It is not defined.

Next when you introduce a new binding with the same name (scope) wherein you call test:

((fn [scope] (test)) (quote dynamic))

A lexically scoped language will return "Is not a valid symbol – LOOKUP-VARIABLE-VALUE scope" as above, because the environment when the definition of test was created does not contain this binding. A dynamically scoped language will return 'dynamic. It does not care about what the value of scope was when test was defined and just looks up the nearest definition. In other words: the lexical environment was not captured.

(The idea for the test was obtained from this Stack Overflow answer, but slightly modified since our language does not know how to evaluate let.

As expected from the above description, the evaluator with the dynamic environment has the following behavior:

Closing remarks

What we have seen above is some nice copy, paste and explaining. For this I was inspired by SICP, and the evaluators of Greg Sexton, Jake McCrary and Mathieu Gauthron.

What we have seen above is an elegant model of computation. Using about seven primitives we can define eval in which we can implement our language.

The idea that an evaluator is just another program (and such a short one) is remarkable. Once you understand how the meta-circular evaluator works, it becomes possible to change the implementation and create interpreters for other languages.

Indeed, new languages are often invented by first writing an evaluator that embeds the new language within an existing high-level language.

(Source)

The fact that Lisp code trees can be changed at runtime or compile time makes it so that it is possible to deeply influence the language. Where in languages like Java you have to wait for a committee to put a new feature into a language, in Lisp you don't have to wait and can implement these features yourself.

One quote (incorrectly stated according to the supposed author but nevertheless instructive) describes the difference between languages without the ability to modify its structure (like Java or APL) and Lisp as follows:

APL is like a beautiful diamond - flawless, beautifully symmetrical. But you can't add anything to it. If you try to glue on another diamond, you don't get a bigger diamond. Lisp is like a ball of mud. Add more and it's still a ball of mud - it still looks like Lisp.

One nice example of the ball of mud idea is the go-routine that is added to Clojure for asynchronous programming (communicating sequential processes). Go also has them, but for Go is it a fundamental language feature. Because the language can be fundamentally and syntactically changed, it could be introduced as a library in Clojure. (See here for more information.)

In SICP among other things the evaluator is extended and modified to become an evaluator for:

And the same idea is used to create an evaluator for machine language and to create a compiler that converts Scheme to a machine language. In SICP it is also explained how the mechanisms works by which procedures call other procedures and return values to their callers (which the meta-circular evaluator borrows from the underlying Lisp).

One of the other things that is missing in the above implementation is a way to define macros, which are used for defining syntax language extensions. I am not so well-versed in them yet. I might play with them in a later post.

I did learn a great deal from the above implementation. I hope it is useful for others as well.

The source code of the evaluators can be found at:

Further reading: